HOME/ SWORDS/

BERSERKER/

DRACULA/ SCIENCE

FICTION / FANTASY /GODS

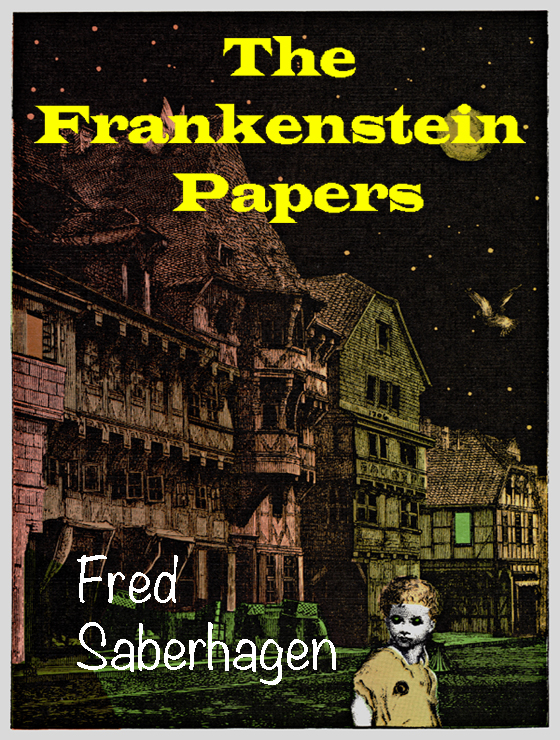

Lightening and thunder flashed over Bavaria as, in his private laboratory, Victor Frankenstein struggled to bring to life a creature constructed from pieces of the dead -- only to find himself confronted by an inhuman monster beyond his control.

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, as well as countless horror movies, has made the legend of Frankenstein and his monster famous throughout the world. But what really happened on that dark and stormy night -- and in the terrible months that followed?

Now, in his own words, the monster reveals the true story of his strange existence. From his harsh awakening in the lab to his desperate struggles in the Arctic, here is a stunning, firsthand account of the tormented relationship between the monster and his creator -- as you have never read it before.

This novel picks up where Mary Shelley's classic tale left off, continuing the narrative from the monster's point of view. Through flashbacks in the monster's journal, Saberhagen also rescrambles the original story in such a way that the monster is absolved of the murders of Victor Frankenstein's brother William and fianceé Elizabeth. The monster sets off on a quest for his own identity that takes him from the Arctic and his first sexual experiments with an "Esquimeaux" to a meeting in Paris with Ben Franklin, whose experiments with electricity led Frankenstein to attempt the monster's initial animation. Throughout, the irrationality of the monster's sheer existence is set against the values and science of Enlightenment Europe. In the tour-de-force ending, rationality triumphs by means of a neat science-fiction twist. [Publishers Weekly]

PROLOGUE

Of Medical Electricity

The firft application of electricity to the cure of diseafes was made by M. Jallabert, profeffor of philofophy at Geneva, on the lockfmith whofe right arm had been paralytic fifteen years … He was brought to M. Jallabert on the 26th of December 1747, and was compleatly cured by the 28th of February 1748. In this interval he was frequently electrified, fparks being taken from the arm, and fometimes the electrical fhock fent through it.

Dr. Franklin and others mention fome paralytic cafes, in which electricity feemed rather to make the patient worfe than better.

Mr. Wilfon cured a woman of deafnefs of feventeen years ftanding—and Mr. Lovet confiders electricity as a fpecific in all cafes of violent pains, obftinate headachs, the fiatica, and the cramp. The toothach, he fays, is generally cured by it in an inftant. He relates a cafe, from Mr. Floyer furgeon at Donchester, of a compleat cure of a gutta ferena; and another of obftinate obftructions in two young women.

Hitherto electricity has been generally applied to the human body either in the method of drawing fparks, as it is called, or, of giving fhocks. But thefe operations are both violent, and though the ftrong concuffion may fuit fome cafes, it may be of differvice in others, where a moderate fimple electrification might have been of ufe.

The great objection to this method is the sediousnefs and expence of the application. But an electrical machine might be contrived to go by wind or water, and a convenient room might be annexed to it, in which a floor might be raifed upon electrics, a perfon might fit down, read, fleep, or even walk about during the electrification.

It were to be willed, that fome phyfician of underftanding and fpirit would provide himfelf with fuch a machine and room. No harm could poffibly be apprehended from electricity, applied in this gentle and intenfible manner, and good effects are at leaft poffible, if not highly probable.

Chapter 1 excerpt

May ? 1782 ?

I bite the bear.

I bit the bear.

I have bitten the white bear, and the taste of its blood has given me strength. Not physical strength—that I have never lacked—but the confidence to manage my own destiny as best I can.

With this confidence, my life begins anew. That I may think anew, and act anew, from this time on, I will write in English, here on this English ship. My command of that language is more than adequate, though how that ever came to be God alone can know.

How I have come to be, God perhaps does not know. It may be that that knowledge is, or was, reserved to one other, who has—or had—more right than God to be called my Creator.

My first object in beginning this journal is to cling to the fierce sense of purpose that has been reborn in me. My second is to try to keep myself sane. Or to restore myself to sanity, if, as sometimes seems to me likely, madness is indeed the true explanation of the situation, or condition, in which I find myself—in which I believe myself to be.

But I verge on babbling. If I am to write at all—and I must write—let me do so coherently.

I have bitten the white bear, and the blood of the bear has given me life. True enough. But if anyone who reads is to understand then I must write of other matters first.

Yes, if I am to assume this task—or therapy—of journal-keeping, then let me at least be methodical about it. A good way to make a beginning, I must believe, would be to give an objective, calm description of myself, my condition, and my surroundings. All else, I believe—I must hope—can be built from that.

My surroundings: I am writing this aboard a ship, using what were undoubtedly once the captain’s notebook and his pencils. He was wise not to trust that ink would remain unfrozen.

I am quite alone, and on such a voyage as I am sure was never contemplated by the captain, or the owners, or the builders of this stout vessel Mary Goode. (The bows are crusted a foot thick with ice, an accumulation perhaps of decades; but the name is plain on many of the papers in this cabin.)

A fire burns in the captain’s little stove, warms my fingers as I write, but I see to write by a small sullen glow of sunlight, emanating from the south—a direction that here encompasses most of the horizon. Little enough of that sunlight finds its way in through the cabin windows, though one of the windows is now free of glass, sealed only with a thin panel of clear ice.

In every direction, lie fields of ice, a world of white unmarked by any work of man except this frozen hulk. What fate may have befallen the particular man on the floor of whose cabin I now sleep—the berth is hopelessly small—or the rest of the crew of the Mary Goode, I can only guess. There is no clue, or if a clue exists I am too concerned with my own condition and my own fate to look for it or think about it. I can imagine them all bound in by ice aboard this ship, until they chose, over the certainty of starvation, the desperate alternative of committing themselves to the ice.

Patience. Write calmly.

I have lost count of how many timeless days I have been aboard this otherwise forsaken hulk. There is, of course, almost no night here at present. And there are times when my memory is confused. I have written above that it is May, because the daylight is still waxing steadily—and perhaps because I am afraid it is already June, with the beginning of the months of darkness soon to come.

I have triumphed over the white bear. What, then, do I need to fear?

Only the discovery of the truth, perhaps?